5 Ways to Identify the List of Scam on Temu

- If you want to know how to determine if a supplier is new, you can see it in the product list, “Seller was founded a few years ago.

- Doing so will take you to the vendor’s sales page, where you can see when the vendor is selling on Temu and view their other products.

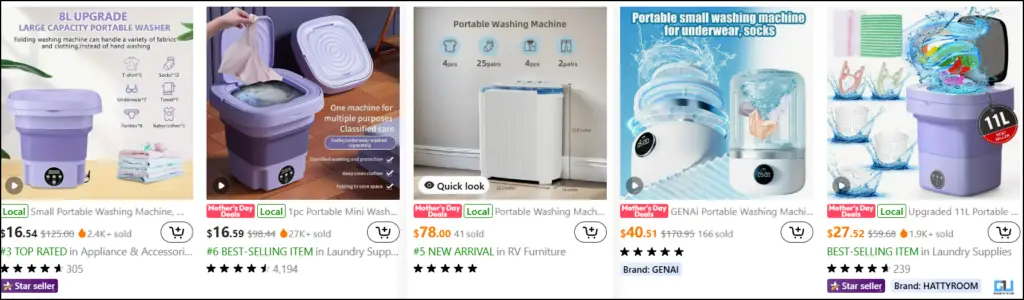

- Multiple suppliers of the same product are the main reason for the number of scams that occur on Temu.

Temu is a shopping paradise for people around the world. All the Pinteresty and unique things you see on feed can be found on Temu. The best part is that the price is always cheaper than most other sites. There are multiple suppliers for the same product, so which supplier would you choose? This chaos has led to many scams. As we all know, when you shop in Temu, you are likely to be scammed. You ask how to prevent it? In this article, I’ll share five tips with you to help you get the product you need without any scams.

Why are people cheated on Temu by scammers?

Multiple suppliers of the same product are the main reason for the number of scams that occur on Temu. You have a lot of vendors who all sell the same products using the same images and videos. This makes it difficult to identify real sellers from dark sellers. Some suppliers may send you different products, or even fake products. If the deal you see is too good, it is too real, please stay away! Temu scams are not limited to merchandise and merchandise; hackers are also trying to steal your credit card information. Another important reason for the shocking scams to increase on Temu is that the supplier’s boarding is unchecked. If a vendor is involved in the process of evaluating its credibility, the number of scams will decrease.

How to Avoid Temu Scam

I’ve purchased items from Temu; luckily, I haven’t been cheated yet. Although it’s just about taking my own precautions, I always follow these five steps, which keeps me from falling into a scam. I’ve listened to them for you below

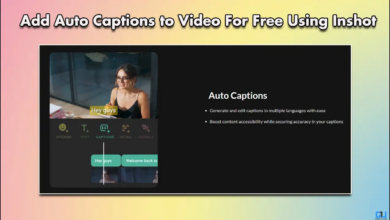

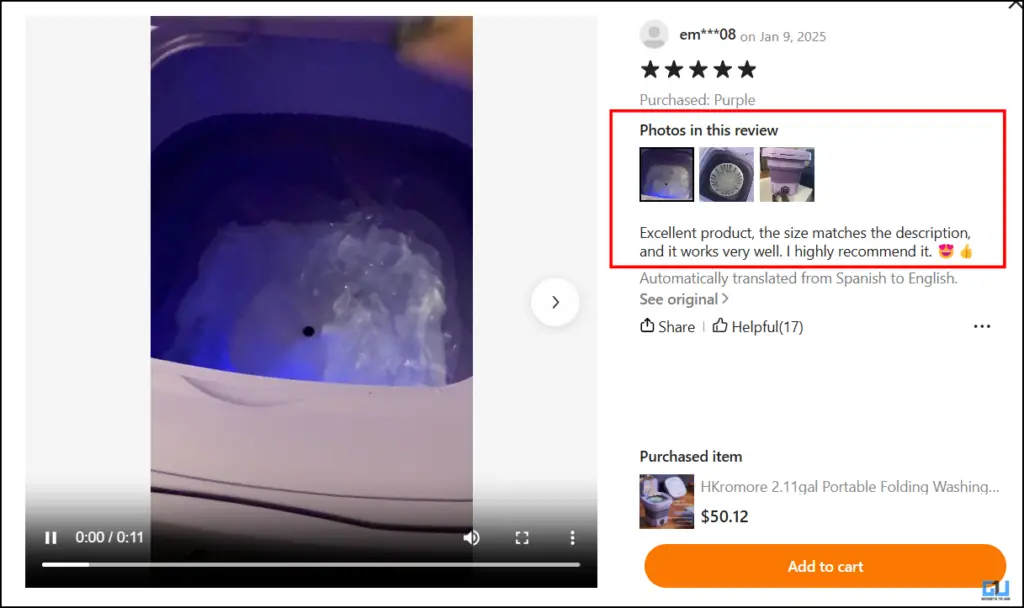

1. Looking for real comments

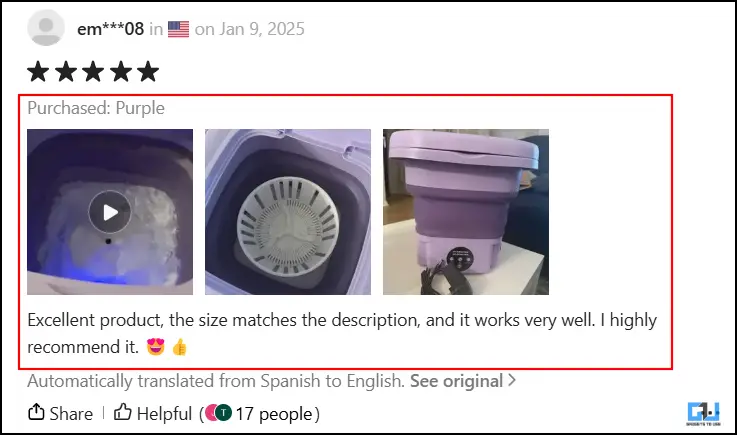

Most obviously, I know you might be able to do this before you buy it, but make sure you do it right. Let me explain, don’t buy products based on positive reviews, make sure you’ve seen reviews, photos and videos.

Also, since there are multiple vendors, make sure you also check their reviews and compare them to those you are considering purchasing. Detailed comments and pictures or videos should be your top priority.

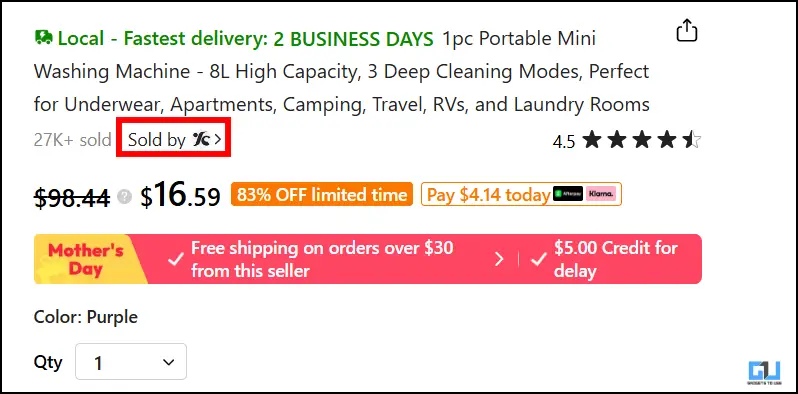

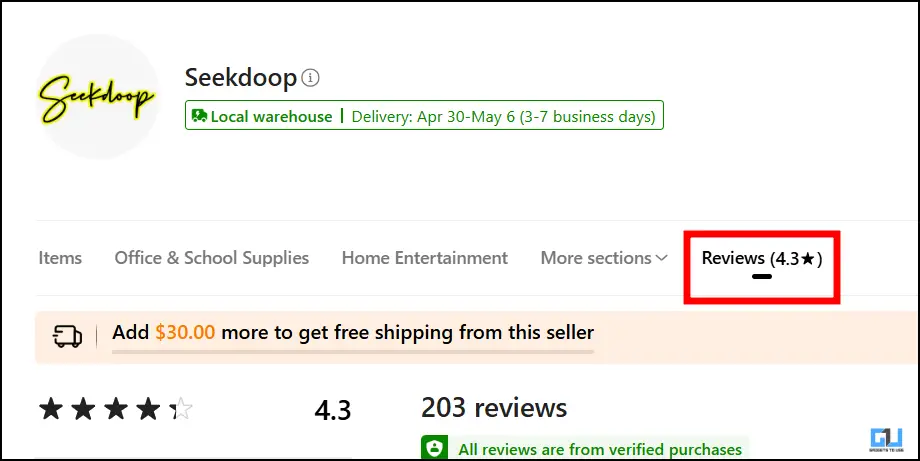

2. View supplier reviews

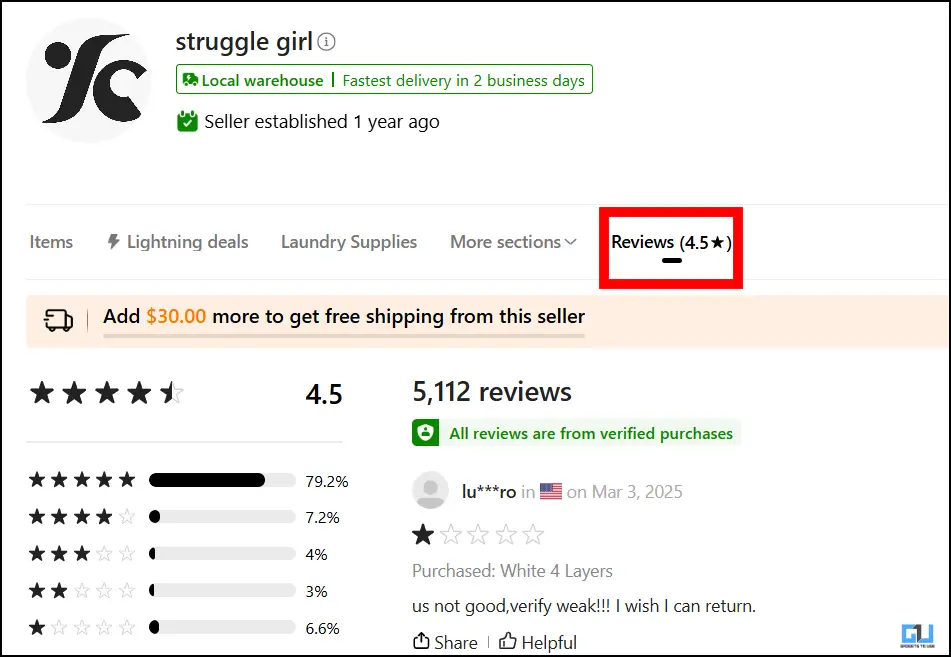

Yes, there are supplier reviews! You may not have checked them before, but now you know, make sure to check them. Since Temu has hundreds of suppliers of products, it is difficult to know which ones are real and which ones are fake. To overcome this, Temu has a supplier rating system. If there are products with high total viewership, you can use the system, but you are not sure. Then, just click on the product and click “sell. ”

Doing so will take you to the vendor’s sales page, where you can see when the vendor is selling on Temu and view their other products. Remember, how long the sales number or supplier has been on Temu, there is no guarantee that you will get real service. Sometimes, new suppliers can also become authorized dealers. Please check the supplier rating before ordering anything.

3. Avoid new sellers

Even if I just say that new sellers can be real, that’s right for 20% of vendors on Temu. The remaining 80% are what you need to pay attention to. If you want to know how to determine if a supplier is new, you can see it under the product list “Seller Built – Built a few years ago”. So make an informed choice.

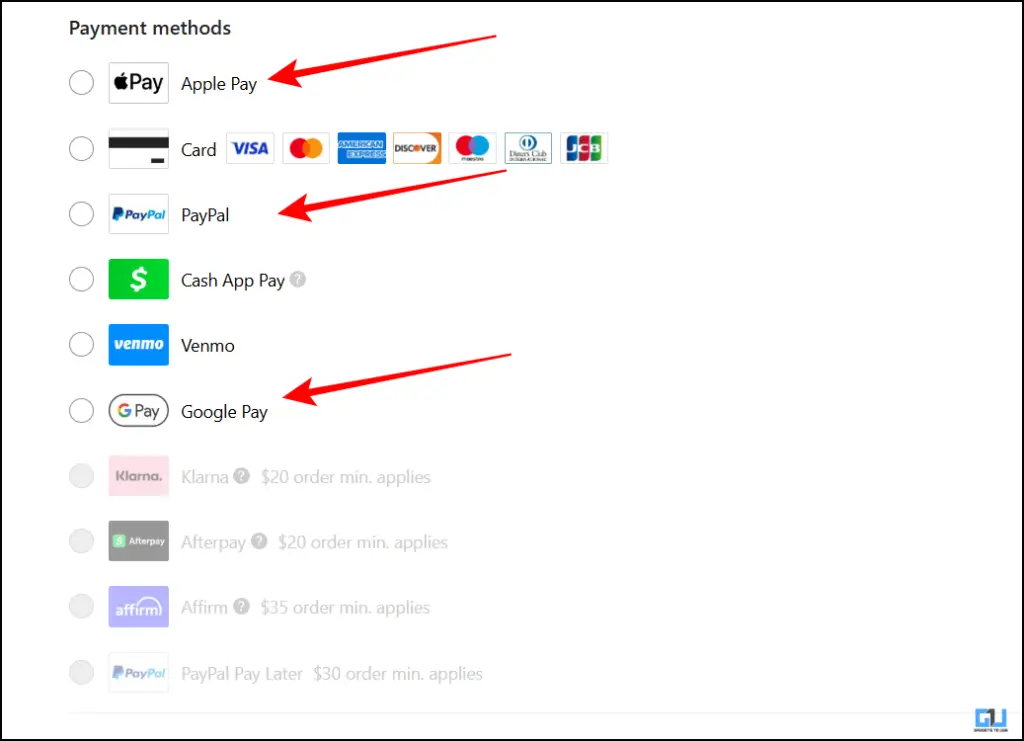

4. Avoid credit/debit card payments

The worst scam on Temu is that your card details are stolen and then used to steal money from your bank account. There are alleged multiple reports of such scams, with a person’s bank account being emptied after shopping in Temu. Although we cannot verify this scam, it is best to avoid indirect payments on the platform.

If you are not sure about using a card, you can use an alternative payment method on Temu. These methods include PayPal, Google Pay and Apple Pay. These are more secure than cards because you need to authenticate before you pay.

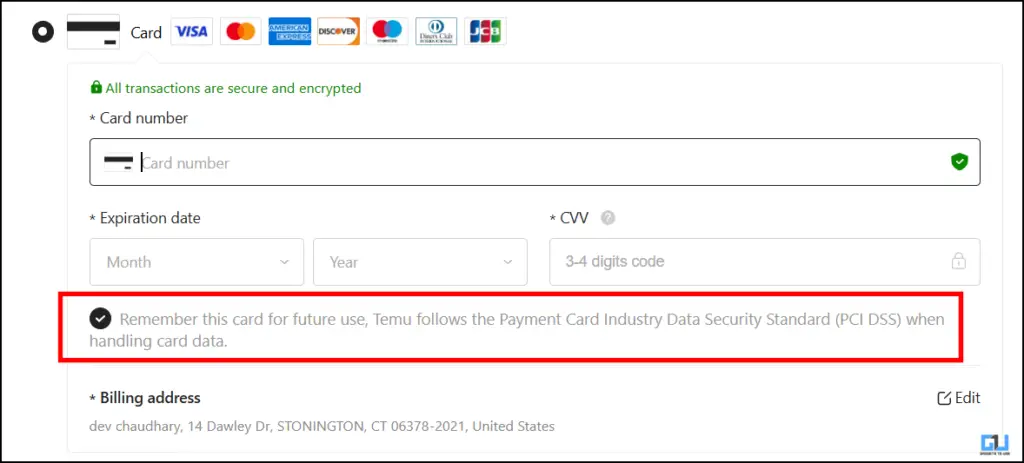

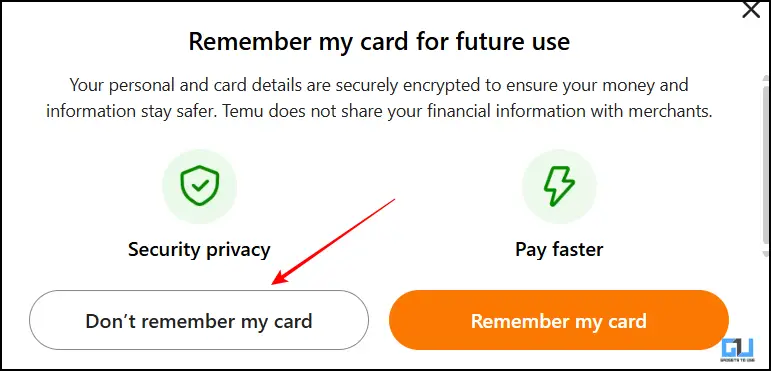

5. Delete your card information

If you don’t have any of the alternative payment methods mentioned above and are forced to use your card, make sure to remove it from the website. I can’t stress enough: Once you pay, you can delete the card from the database.

Temu is full of scams, but people continue to use it and order items from it. However, before ordering anything, I will always use my five-step method to make sure I’m not cheated. the same as you.

FAQ

Q: Does Temu have customer service?

Temu does have 24/7 contact support services. However, according to the comments, it is not very helpful and there is no guarantee in terms of the solution.

Q: Do you get fake products on Temu?

Yes, and no, Temu is an international online store with multiple suppliers selling its products. Products are not fake; some of them can be copies of the original product, but it depends only on the supplier.

Summarize

Temu is an online store, it’s great if you want to buy something at an affordable price. You can get almost anything on Temu, which is great. However, the number of scams is also shocking. This is mainly because there are many vendors and there is no proper verification method. You need to be very careful when placing an order in Temu. Make sure you follow the steps discussed in the article.

You can also follow us for instant tech news Google News Or comments about tips and tricks, smartphones and gadgets, please join Gadgetstouse Telegram Groupor subscribe Gadgetstouse YouTube Channel About the latest review video.

Was this article helpful?

YesNo